In

2014, for the third year in a row, Chairman Stu gathered together a

group of brave bloggers to tackle the task of shadowing the Independent

Foreign Fiction Prize. It's not a task for the faint of heart - in

addition to having to second-guess the strange decisions of the 'real' panel,

the foolhardy volunteers undertook a voyage around the literary world, all in a

matter of months...

On

our journey around the globe, we started off by eavesdropping on some private

conversations in Madrid, before narrowly avoiding trouble with the locals in

Naples. A quick flight northwards, and we were in Iceland, traipsing over

the snowy mountains and driving around the iconic ring road - with a child in

tow. Then it was time to head south to Sweden and Norway, where we had a

few drinks (and a lot of soul searching) with a man who tended to talk about

himself a lot.

Next,

it was off to Germany, where we almost had mussels for dinner, before spending

some time with an unusual family on the other side of the wall. After

another brief bite to eat in Poland, we headed eastwards to reminisce with some

old friends in Russia - unfortunately, the weather wasn't getting any better.

We

finally left the snow and ice behind, only to be welcomed in Baghdad by guns

and bombs. Nevertheless, we stayed there long enough to learn a little

about the customs involved in washing the dead, and by the time we got to

Jerusalem, we were starting to have a bit of an identity crisis...

Still,

we pressed on, taking a watery route through China to avoid the keen eye of the

family planning officials, finally making it across the sea to Japan.

Having arrived in Tokyo just in time to witness a series of bizarre

'accidents', we rounded off the trip by going for a drink (or twelve) at a

local bar with a strangely well-matched couple - and then it was time to come

home :)

Of

course, there was a method to all this madness, as our journey helped us to

eliminate all the pretenders and identify this year's cream of the crop.

And the end result? This year's winner of the Shadow Independent

Foreign Fiction Prize is:

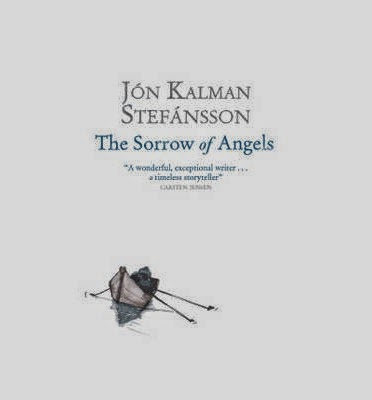

The Sorrow of Angels by Jón Kalman Stefánsson

(translated

by Philip Roughton, published by MacLehose Press)

This

was a very popular (and almost unanimous) winner, a novel which stood out

amongst a great collection of books. We all loved the beautiful, poetic

prose, and the developing relationship between the two main characters - the

taciturn giant, Jens, and the curious, talkative boy - was excellently written.

Well done to all involved with the book - writer, translator, publisher and

everyone else :)

Some

final thoughts to leave you with...

-

Our six judges read a total of 83 books (an average of almost fourteen per

person), and ten of the books were read and reviewed by all six of us.

-

This was our third year of shadowing the prize and the third time in a row that

we've chosen a different winner to the 'experts'.

-

After the 2012 Shadow Winner (Sjón's From the Mouth of the Whale),

that makes it two wins out of three for Iceland - Til hamingju!

-

There is something new about this year's verdict - it's the first time we've

chosen a winner which didn't even make the 'real' shortlist...