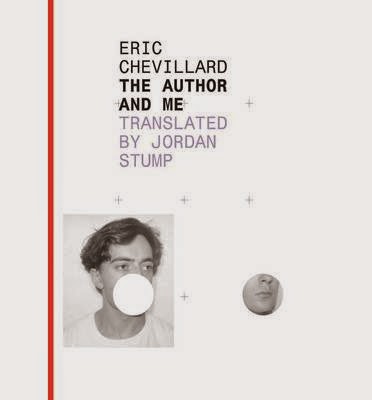

In early June I reviewed Eric Chevillard’s “Prehistoric

Times” from Archipelago Press, “postmodernist literature”, “France’s foremost

absurdist” were the quotes at that time. From a different publishing house (Dalkey

Archive this time) but the absurdist things have not changed. "The author and me" is due for release tomorrow.

Our protagonist is a first person (un-named?) narrator who

is not the author (as he goes to great pains to point this out in the numerous,

well 40 to be exact, footnotes), or is he?

The theme of the work is a gentleman having lunch with

Mademoiselle and being enraged by being served cauliflower gratin instead of

tout amandine.

Disappointment...despair...rage!

The urge to kill then comes over you, Mademoiselle, and above all the secret

temptations of torture. All at one you find yourself thinking of the many

possible but overlooked uses of the most rudimentary tools. And this time your

tongs won’t undo you hammer’s insistent labours. For once – how wonderful! –

your tongs and your hammer will be working as one. Something sublime may well

be in the offing, exquisite in its inventiveness.

Have you ever longed to strangle

someone, Mademoiselle?

Besides me, I mean?

Your pursed lips say no – not even

me? Really? Oh, but in that case you must never have endured so cruel and

agonizing an experience. Just imagine, imagine a beautiful trout, still

wriggling only the day before, as at one with the stream as the current, the

muscle of the light, the intelligence of the water, its tender flesh perfumed

with a little spray of lemon, sprinkled with finely slivered almonds,

diaphanous hosts toasted golden brown in sizzling butter...

Just you take a whiff of that.

But what’s this? What on earth

can that be? That stench?

Unholy God!

They say disappointment is bitter

– I find it more insipid than anything else.

It’s cauliflower gratin!

To say this is an absurd book would probably be an

understatement, we have our author addressing us (quite frequently) to point

out that he is not the character in the novel, his life experience being quite

different than his character’s. We have his describing the metaphysical

pleasure of reading itself, the pace according to the writer, and followed by a

footnote with advice on how to approach, and at what speed, Chevillard himself.

We have all number of explanations of the human condition:

(Nevertheless, the cafe had its regulars. They nodded on spotting each

other. Some swapped banalities and information on the meteorological conditions.

About as useful as reminding each other what they were wearing that day. Empty

words, more an avoidance strategy than anything else. Thus did the regulars

keep each other at a distance. The clouds served as a buffer.)12

12 This is also the reason for

the screen of politesse that the author unfolds between himself and others. He

even adds a certain unctuousness, to prevent any friction. Can harmony exist

without distance? Obeying an impersonal code, we efface anything that makes us

stand out. We become any man in the street. In the end, it’s as if we weren’t

there at all – and such is indeed the author’s most constant desire: to be

somewhere else, far from here. What to do with the hyper-presence of those

boors who refuse to fade into the background, or at least suck in their

stomachs a little? Civility is a game of capes and passes by which we dodge the

bull, which is more often a talkative neighbour than a savage beast blowing

steam from its nostrils.

Nothing escapes the wrath of Chevillard in this one, in “Prehistoric

Times” he put evolution in reverse, here he holds a mirror up to the day to day

banalities, points out how absurd our behaviour is, and similarly shows us that

human existence is trite, miniscule, and irrelevant:

(As a general rule, however, the most talkative were those sitting alone.

Telecommunications had made spectacular progress. Everyone was compulsively

fingering his mobile phone – the term was accurate, if slightly deceptive. What

had become mobile were the house, the workplace, the solid block formed of

family, friends, and acquaintances. Mobil, but heavy as ever, and people’s

backs bent accordingly under the weight. Sitting at cafe tables or walking down

the street, hunchbacks everywhere. All that scoliosis, all those soliloquies

betrayed the imposture and untruth of lives risen up from the void, written on

the wind. The deluge’s great wave was sweeping those drowned souls away, no one

knew where.) 15

15 It’s finally come to pass, at

long last we have in our power – or almost – the magic wand of fairy tales:

those multifunction telephones that know everything and work all manner of

wonders, soon to include teleportation. Of course, by this short-circuiting of

all distance (which once mapped out human space) and delay (which one

structured human time) we’re also remaking our bodies and minds. We’re

mutating, flocking toward the future, sheep that we are. Paradoxically transformed

into dumb beasts, stripped of the power of concentration, motivated by

impatience alone, by immediate necessities, by imperious, rudimentary instincts.

And so we see the rise, in the flesh, of the man so long dreamt of by science

fiction.

This work is, of course, not everybody’s cup of tea, there

will be people who are infuriated by the ramblings, the lectures, the demeaning

nature. The conversations not marked, may distract, the internal musings of our

author and his character could enthral or enrage you, the self centeredness of

both characters could make you smile or wince. But there is no doubting that

this is a thinking piece of writing, pushing the boundaries of the expected

norms of the written word, blurring the lines between narrator, protagonist and

author. Our writer attempting to deconstruct the formation of a perfect novel.

One for slow contemplation and discovery, a work on the

edge, skillful, surprising, joyous, repetitive infuriating and mundane all at

the same time. One thing you will be guaranteed of though – you’ll never look

at cauliflower the same way again.

No comments:

Post a Comment